You don’t have to know a ton about tornadoes to know that the radar images from last night’s thankfully-very-rural tornado near Hollister, Oklahoma are unusual. I have seen a lot of mentions of this storm online from other weather nerds but, unfortunately, they all look similar to this:

While this is great information, I don’t yet understand all of the industry gobblety-gook terminology. That means tweets like this are essentially useless to people like myself who are new to the hobby. Though my intention is to eventually make a post with vocabulary and the definitions I have found across the web, let’s see if I can break this one down into easy to understand terms.

- RFD Surge initiate[s] a strong tornado

RFD stands for Rear Flank Downdraft. The official definition (thanks Wikipedia) is that this is a region of dry air wrapping around the back of a mesocyclone in a supercell thunderstorm. A mesocyclone is an organized area of rotation a few miles up in the atmosphere.

As rainfall increases within the supercell, an area of quickly descending (falling) air becomes the RFD, which accelerates as it gets closer to the ground. This action works to pull the rotation of the mesocyclone to the ground, forming a tornado. There are some thermodynamics happening that cause the condensation funnel, or visible tornado. In the case of the tornado we’re discussing today, this happened very quickly and intensely.

2. TVS with GTG shear of 260+ MPH (600 FT beam height)

Let’s start with the acronyms here (I hate acronyms for their lack of lending context): TVS = Tornado Vortex Signature. This is the radar velocity pattern that indicates a region of intense concentrated rotation. GTG = gate to gate. This is the change of wind speed and/or direction across the two gates of inbound and outbound velocities (the circulation within a storm). A gate is a pixel on a radar display. The Gate to Gate shear is not a measure of windspeed and does not indicate the strength of the storm.

So why is 260+ MPH impressive? Because it indicates that there was a difference of 260 MPH between the inbound and outbound velocity, which is a LOT. I was searching for a comparison to demonstrate how much velocity this is, but there’s a lot of math to convert meters per second and knots and kilometers and I’m not doing it. Sorry. Also, beam height? I got nothin’ (meaning I couldn’t get a good answer via Google).

3. Tornado retrograded as it occluded

To say that the tornado retrograded means that it began to spin in the opposite direction of what is normal given the hemisphere. Remember when you were a kid and you learned that when you flush the toilet in Australia, the water swirls in a different direction? Same with tornados, in that they rotate in different directions depending on the hemisphere. That’s more of just a fun fact than something that is relevant to this particular statement.

Occlusion can refer to the central downdraft that can form in the mesocyclone, which is called occlusion downdraft (OD). Tornadoes can form in the region between the occlusion downdraft and the mesocyclone updraft, similar to suction vortices forming in a tornado. As one tornado dissipates, occlusion can cause a secondary tornado to form in more favorable part of the storm cell.

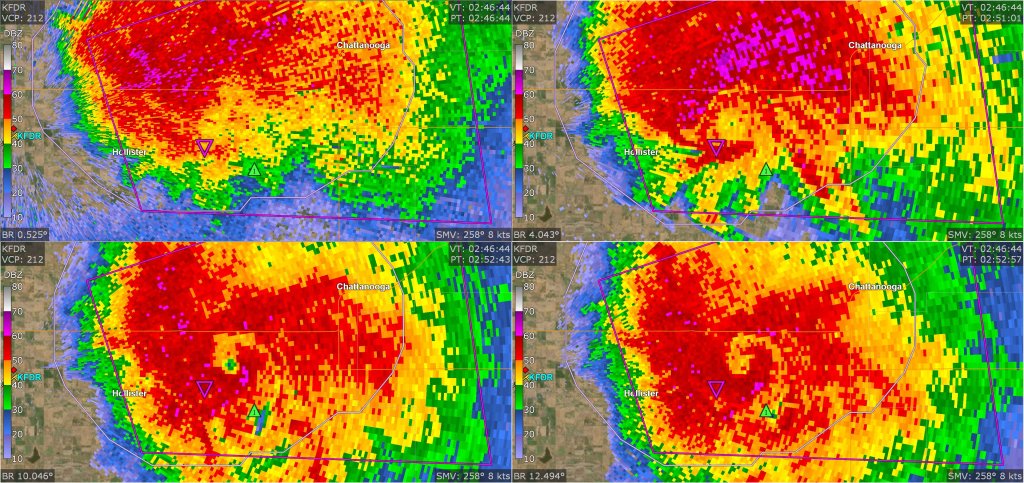

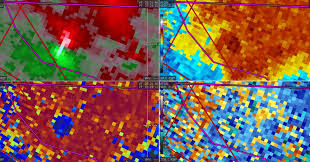

4. “Hurricane Eye” BWER

Here’s another acronym: Bounded Weak Echo Region. In this context, it refers to the weak radar signal in the center of the tornado. This sometimes will turn into a hook echo, which is a classic appearance of a tornado on radar. Here’s what this storm’s BWER looked like:

5. Strong anticylconic tornado emerge to the south

Remember earlier when I mentioned that the toilet water swirls differently in Australia? Remember how that was the same with tornadoes? That’s called “anticyclonic,” meaning the rotation of the tornado is turning in the opposite direction.

That’s the breakdown of one, highly-technical tweet from someone a whole lot smarter than me. I hope you learned something new!

Leave a comment